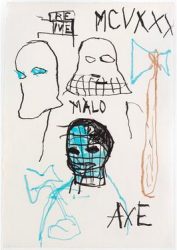

Image courtesy of Nuestro Stories.

Thirty-four years ago, at just 27 years old, a heroin overdose ended the life of Puerto Rican/Haitian American painter Jean-Michel Basquiat.

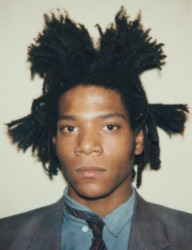

Known as the “Jimi Hendrix of the art world,” his professional career lasted only nine years. Still, it was enough to elevate Basquiat to the pantheon of neo-expressionists and label him one of the most influential artists of the 20th century.

Today, his work is still relevant and sells for millions of dollars at auction.

There is just one problem — he was misidentified by the media. It anointed him the first international African-American artist when he was the first American artist of Caribbean descent.

The story of a genius

The Jean-Michel Basquiat the world knew was a caricature — a revolutionary artist, dreadlocks suspended in the air, wearing paint-splattered Armani suits, barefoot and beautiful. But his narrative and his work came from his Puerto Rican and Haitian heritage.

He was born into a middle-class family. His father, Gerard, was a Haitian immigrant, and Mathilde, his mother, was a Boricua from Brooklyn. According to Basquiat, his father was physically abusive, and his mother suffered from mental illness and was hospitalized for depression.

But it was Matilde who took young Basquiat to the Museum of Modern Art, bought him art supplies, and gave him a copy of Gray’s Anatomy. The anatomical drawings would be a key to the Basquiat narrative and Spanish words like pollo frito, sangre, and peligroso.

At 17, he ran away to a New York City that was cracking up. This decaying metropolis city was made up of Puerto Rican and Dominican neighborhoods.

Boricua flags fluttered from abandoned buildings that resembled cracked teeth and the scenario of a crack and heroin epidemic.

The streets and alleyways became his canvas. Walls, doors, sidewalks — any object interesting enough to be transformed into a story. This is also where Samo@ (same old shit) was born, the brainchild of Basquiat and his teenage friend, Al Diaz, another New Yorker of Puerto Rican heritage. It mocked “bogusness” in a city they saw full of middle-class wannabes.

Basquiat started by selling his drawings for $50 a pop and graduated to selling canvases so fast that the paint was not even dry. He worried that he had become a “gallery mascot.”

At the end of his life, Basquiat’s paintings were selling for about $25,000. Buyers were the Whitney Museum and the Museum of Modern Art. Still, neither of these grand institutions ever gave Basquiat an exhibition. The experience made him bitter.

“They still call me a graffiti artist,” he told Vanity Fair at the time. “They don’t call Keith or Kenny graffiti artists anymore.”

Few understood who Basquiat was, but they all wanted to be like him or be around him. They still do.

https://nuestrostories.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Susanne-182×250.jpeg