“If Spaniards are in Heaven, I’ll go to hell” is Hatuey’s last message to the world. It was a defiant stand against brutality, hypocrisy, and forced conversion. Sure, you may not know his name, but you should. Hatuey was a Taíno leader from Hispaniola—what we now call the Dominican Republic and Haiti—who was one of the very first Indigenous people to stand up and fight back against European colonization in the Americas.

While history tends to celebrate the conquerors, it rarely remembers the few conquered who had the courage to resist. Hatuey was one of those few. We don’t know much about his early life, but here’s what we do know: when the Spanish tightened their grip on the Caribbean, Hatuey didn’t run. He organized. He warned. He led.

And, yes, his story is even on Netflix.

Telling Hatuey’s Lost Story

Described by historian William Loren Katz as “the first prominent freedom fighter of the Americas,” Hatuey’s name does not appear in most textbooks. But his courage and his clarity in the face of conquest should be remembered.

“Hatuey’s armed resistance began on the island of Hispaniola during the age of Columbus, and probably increased after 1502 when a fleet of 30 Spanish ships brought the new Governor Nicolas de Ovando, hundreds of Spanish settlers, and an estimated 100 enslaved Africans to Hispaniola,” the Zinn Education Project explains.

When Ovando complained to King Ferdinand that enslaved Africans “fled among the Indians, taught them bad customs, and could not be captured,” what he may have been describing, according to Katz, was “the formation of the first American rainbow coalition.” Hatuey and his people welcomed the escaped Africans as allies, uniting against a shared enemy: a system rooted in gold, greed, and violence.

Hatuey’s Mission Across the Sea

In 1511, Hatuey led 400 followers in canoes from Hispaniola to Cuba. His goal was urgent: to warn fellow Indigenous communities of what was coming, and to unite them in resistance.

In Cuba, his words were recorded by Dominican friar Bartolomé de Las Casas. Hatuey warned that the Spaniards “worship gold,” “fight and kill,” and “usurp our land and make us slaves.” His message was direct and defiant: “For gold, slaves, and land they fight and kill; for these they persecute us, and that is why we have to throw them into the sea.”

Hatuey was a warrior and a visionary organizer, leading what Katz calls “the first pan-American resistance struggle.”

Three Months of Defiance in Baracoa

According to “The Mysteries of Latin America Podcast,” hosted by Andrew Colón, Hatuey “was said to be a compelling public speaker, and the Spanish friar and missionary Bartolomé de las Casas later attributed these words to Hatuey: ‘These tyrants tell us they worship a god of peace and equality, but they usurp our lands and make us their slaves. They speak to us of an immortal soul and its eternal rewards and punishments, but they steal our belongings, seduce our women, and violate our daughters. Unable to match us in courage, these cowards cover themselves with iron that our weapons cannot break.’”

Hatuey began mobilizing resistance in Cuba, Spanish forces led by Diego Velásquez landed. Among them was Hernán Cortés, who would later lead the conquest of Mexico. Hatuey responded with a strategy of guerrilla warfare, attacking, dispersing into the hills, and regrouping to strike again.

This strategy worked. For three months, Spanish forces were unable to move beyond their stronghold in Baracoa. They were outmaneuvered, uncertain, and afraid.

But eventually, the Spanish launched a full offensive that overwhelmed Hatuey’s forces. He was captured and sentenced to death.

A Final Act of Defiance

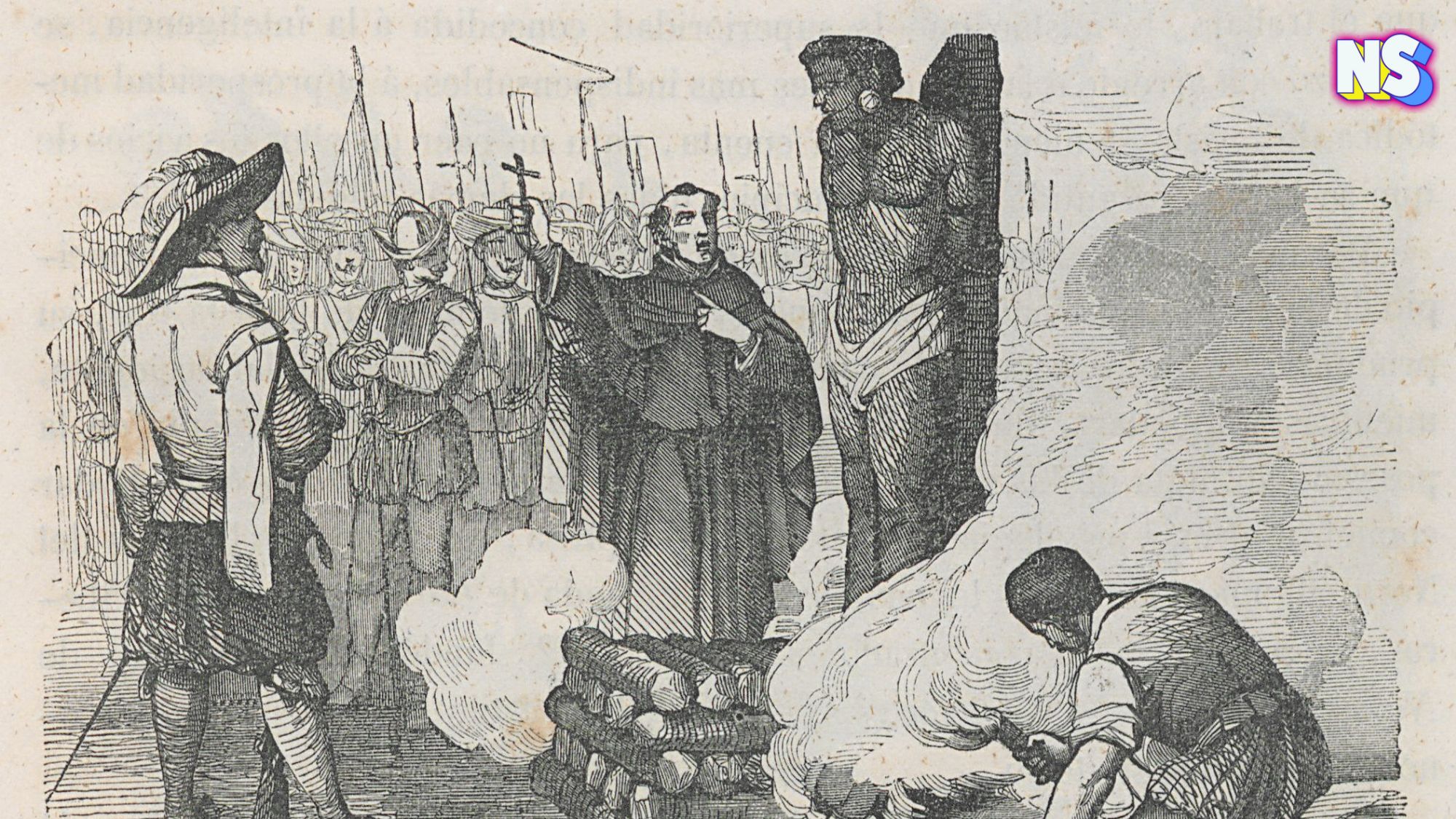

In 1512, Hatuey was led to a public execution. Before he was burned at the stake, history tells us that a Franciscan friar offered him salvation through Christianity. He explained that if Hatuey accepted the Christian faith, he could enter heaven.

Hatuey asked if Spaniards also went to heaven. When the friar said yes, Hatuey gave his final answer: he would rather go to hell.

In that single moment, Hatuey exposed the deep hypocrisy of his executioners. His words were not just a rejection of forced conversion—they were a rejection of a system that claimed moral authority while enacting unspeakable violence.

The Legacy of Hatuey

Today, Hatuey is remembered in Cuba as a national hero. A statue in Baracoa honors him. And the story of his execution is portrayed in the Spanish movie También la Lluvia (Even the Rain), available on Netflix.

“I think it’s even more powerful than the final scenes of ‘Braveheart’ or ‘Gladiator,’” the The Mysteries of Latin America Podcast says.

RELATED POST: Honoring Emerson Romero

Many beer drinkers may also recognize the name Hatuey from a bottle, poured into glasses for nearly a century.

Back in 1927, Cuba’s oldest brewery, Cervecería Hatuey, named its signature beer after the Taíno leader. The beer quickly became a Cuban favorite—a smooth, crisp lager that came to symbolize national pride and resistance. But after the Cuban Revolution, the brewery was nationalized and Hatuey beer vanished for decades.

Then, in the 1990s, the Bacardí family, who had been exiled from Cuba, brought it back, brewing it in the U.S. and reintroducing it to a new generation.

So here’s a toast to the rebel with a cause, Hatuey. May his name one day live in our history books, and may his story continue to give hope to the oppressed … and those who dare to resist.