Somewhere between the late 1980s and early ’90s, 15 colonial-era documents quietly vanished from Mexico’s national archives. No one noticed it at the time, but a 16th-century manuscript, signed by the man who toppled the Aztec Empire, Hernán Cortés, went missing. Now, one of those pages (page 28, to be exact) is finally back where it belongs.

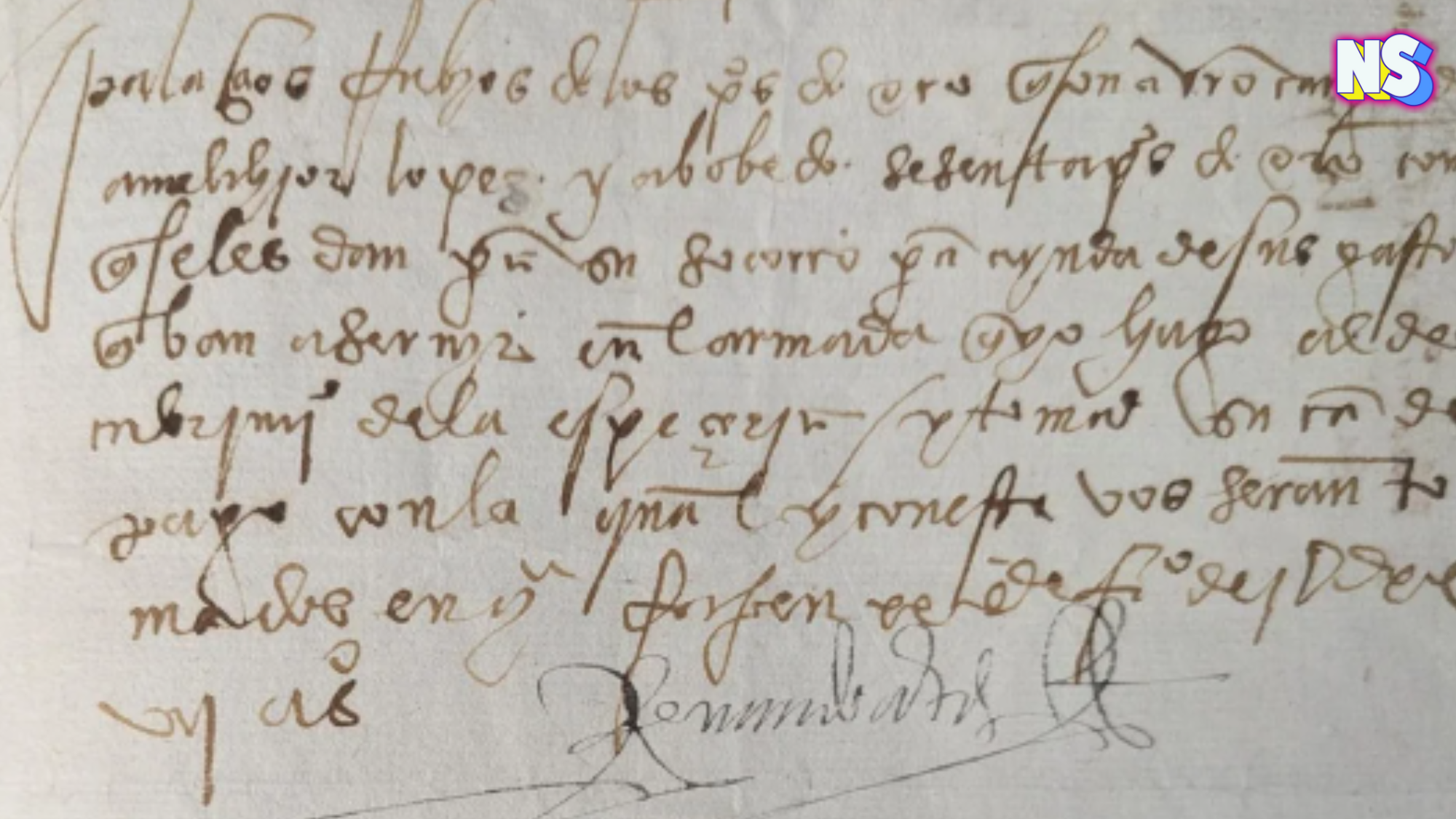

Earlier this week, the FBI officially returned the 498-year-old document to El Archivo General de la Nación in Mexico City. Dated February 20, 1527, the page includes a short, but revealing, note on the “payment of pesos of common gold for expenses,” signed by Cortés himself. In other words, it’s a receipt from the early days of the empire.

“This is an original handwritten page,” said FBI Special Agent Jessica Dittmer, who works with the agency’s Art Crime Team. “It really gives a lot of flavor as to the planning and preparation for territory back then.”

And it was never supposed to leave Mexico’s custody.

How It Was Stolen and Found

Archivists at Mexico’s national archives first noticed the missing pages in 1993, while microfilming a collection of Cortés documents. That’s when they realized 15 pages had been ripped from the bound manuscript. One clue stood out: a wax numbering system used briefly between 1985 and 1986 was still visible on the pages that remained. That narrowed the timeline. The documents had been taken sometime between 1985 and October 1993.

In 2023, Mexican officials asked the FBI for help locating page 28. According to Smithsonian, the archive’s detailed records, which included descriptions of the tears, gave investigators something rare: a trail.

The FBI used open-source research to track the missing page to the United States. Officials haven’t said who had it or how it resurfaced. But the document had passed through multiple hands since its theft, and no charges will be filed.

Still, its return is being hailed as a symbolic win.

“Pieces like this are considered protected cultural property and represent valuable moments in Mexico’s history,” said Dittmer. “This is something that the Mexicans have in their archives for the purpose of understanding history better.”

RELATED POST: Iztaccíhuatl & Popocatépetl: A Tale of Eternal Love

FBI supervisory special agent, FBI-NYPD Major Theft Task Force, Veh Bezdikian, added, “We know how important it is for the United States to stay ahead of this, to support our foreign partners, and to try and make an impact as it relates to the trafficking of these artistic works and antiquities.”

Who Was Hernán Cortés?

To understand why all of this matters, you have to know the story behind the signature. Hernán Cortés arrived on the shores of what’s now Mexico in 1519. Within two years, he and his army, along with European disease and military alliances with Indigenous rivals, brought down the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán. He went from uninvited explorer to imperial governor in record time.

According to the Smithsonian, by 1527, when this document was signed, Cortés was running vast swaths of land for the Spanish crown. He wielded power through ink and iron: letters, decrees, receipts, and battles. This page is one of the few surviving records that links directly to those early years of colonization.

This Isn’t the First Hernan Cortés Page the FBI Recovered

Page 28 is the second missing Cortés document the FBI has helped return. As the Smithsonian explains, in 2022, another signed manuscript surfaced at RR Auction in Massachusetts. That one, dated April 27, 1527, was a payment order for 12 gold pesos’ worth of rose sugar.

“The document measures just 21.5 by 15 centimeters (8.4 by 6 inches),” El Pais explained. “It is a payment order given by Hernán Cortés to his steward, Nicolás de Palacios Rubios, to buy the equivalent of 12 gold pesos of ‘pink sugar,’ possibly during an expedition in the current territory of Honduras. On the front are the purchase instructions in old Spanish and on the back, the confirmation from the owner of an apothecary’s shop, Maestre Francisco, that he received payment.”

Mexican officials recognized this document just 10 days before bidding closed and alerted the feds.

“As soon as we got contacted, we put a stop to the sale,” attorney Mark S. Zaid, who represented the auction house, told the New York Times. “We notified the consignor, and there was no issue from them.”

The following year, the rose sugar letter was repatriated during a formal ceremony in Mexico.

“Usually, people are surprised when they find out that the items they have are stolen,” FBI Special Agent Kristin Koch told El País. “Many times, when they realize the cultural value they have for the countries of origin or the original owners, they are willing to part with the object.”

Why It Matters Now

Since launching in 2004, the FBI’s Art Crime Team has recovered more than 20,000 stolen items, worth over $1 billion. It’s cultural justice built piece by piece.

Page 28 is just one of 15 stolen Cortés manuscripts. Only two have been found so far. The others? They’re still missing, possibly tucked in a private collection or passed down unknowingly.

But thanks to meticulous archivists, dogged international cooperation, and a few decades’ worth of good old-fashioned detective work, Mexico is reclaiming its past, one page, one signature, and one story at a time.