It’s a symbol. It’s an icon. It’s an outcast.

It’s the ñ. The controversial, and sometimes forgotten, 15th letter of the Spanish alphabet. But why does a letter with a wavy line on top garner up so much attention?

One could blame it all on the ñ origin story … which would only be a partially correct conclusion. Actually understanding the letter’s long, and difficult, journey to modern times holds more clues which unveil the world’s fascination with the ñ.

The History of a Letter

ABCs should be as easy as, well, saying your ABCs. But if you’re a Spanish speaker explaining the extra letter in your alphabet, things can get more complicated.

What’s in a letter? Well, the letter “ñ” is a distinctive symbol in the Spanish language and is used to represent the sound of the letter “n” with a tilde (~) placed on top.

Heck, there could be no español or España without the n with the eyebrow on top. The sound it makes is “en-yay.”

It’s believed to have originated in the Middle Ages as a result of the evolution of the Latin language. During the Middle Ages, scribes and scholars in Spain began to use various techniques to denote certain sounds and distinguish them from existing letters.

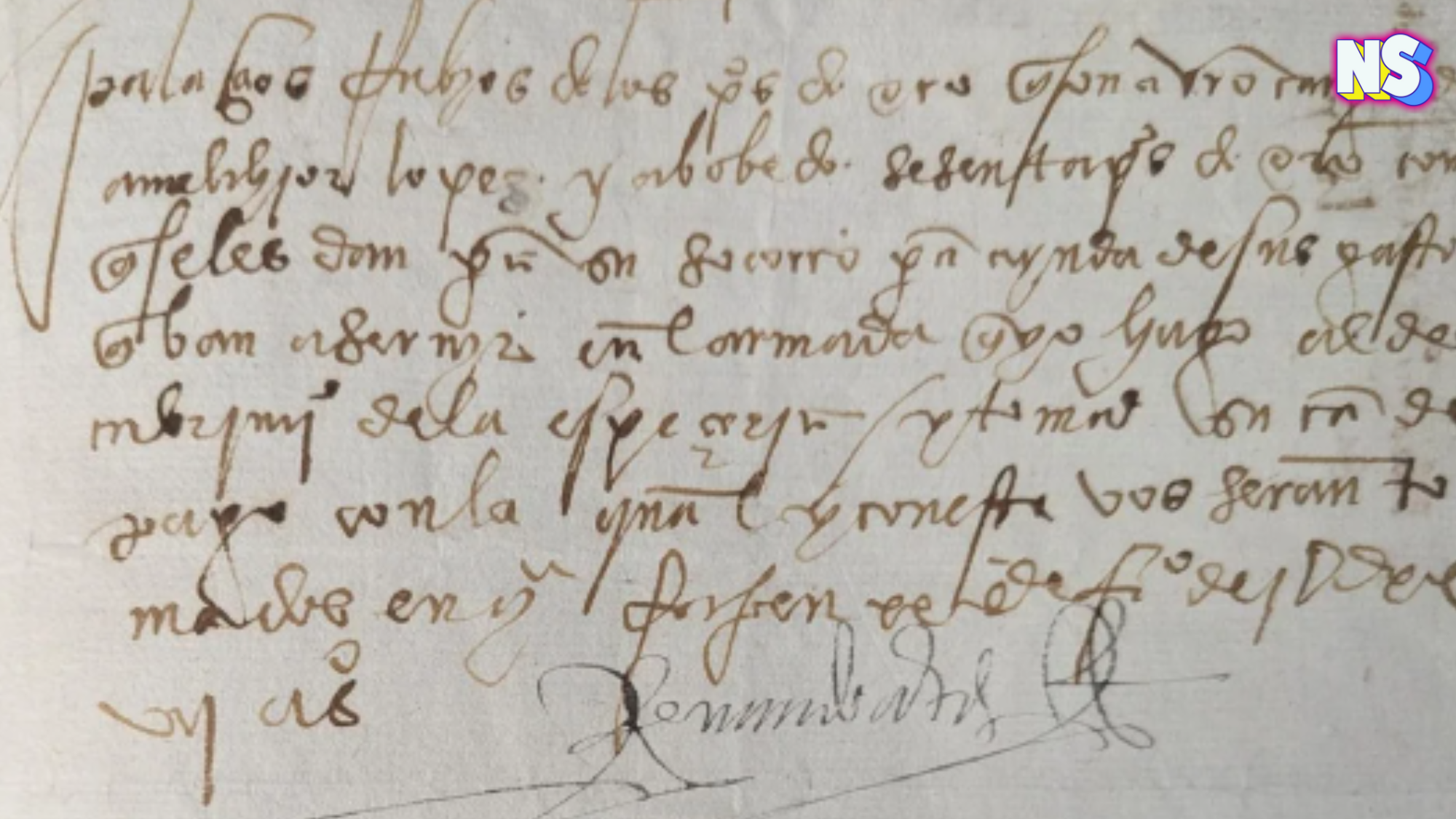

In the case of the “ñ” sound, it emerged as a contraction of two letters: “n” and “y,” and also the “n” and “n” combination. These scribes, or monks given the task of writing documents before the invention of the printing press in around 1436, had to find a way to cut down on the tedious nn.

The ñ became a substitute, or shortcut, for having to write two letters.

Fun Ñ Fact: On October 2, 2007, the ñ, as well as other tildes, debuted in email addresses and web domains. (Source: El Pais.)

In the 13th century, King Alfonso X of Castile and León ordered a spelling reform “as part of his policy of linguistic unification,” according to Spain’s official newspaper El Pais. The monarch (known as a great reader, writer and intellectual), introduced the ñ as a preferred option in writing, setting the first rules of the Spanish language.

When the use of ñ became widespread across the Iberian peninsula, the letter went on to appear in the first Spanish grammar book in 1492.

Yet, despite being used for over hundreds of years, the letter ñ was first included in the dictionary of the Royal Spanish Academy (RAE) in 1803.

The Ancient Accent Mark

The tilde (~), known in Spanish as a virgulilla, was originally used as a shorthand mark known as a “virgula suspensiva” to indicate that a letter had been omitted.

In the case of the “ñ,” the tilde was placed over the letter “n” to represent the contraction of “nn” into a single sound.

Over time, the symbol became more standardized and widely used, eventually being recognized as a distinct letter in its own right. It became an integral part of the Spanish alphabet and is now considered a separate letter, coming after “n” and before “o” in the alphabetical order.

It is widely used in Spanish to represent specific sounds and appears in numerous Spanish words, such as “niño” (child) and “mañana” (tomorrow).

The accent in the shape of a wave itself has been a staple in writing since 1000 A.D. One of the accent’s first appearances shows up in The Doomsday Book of 1086, also known as the Domesday Book, a historical record of land ownership and property holdings in England.

The tilde was used alone (without an “n” underneath it) to show omitted letters, much like the one apostrophe (‘) is used today. Soon the tilde can be seen in other languages and certain linguistic contexts to mark an alternative pronunciation, historical variation, or archaic form of a word.

Let’s break it down more: a tilde is a diacritical mark (~) commonly used in various languages, including Spanish, Portuguese, and others. And it appears as a small wavy line placed above a letter or character. The term “tilde” comes from the Spanish word for “swung dash.”

In different languages, the tilde can serve different purposes. In Spanish (as we’ve pointed out already) the tilde (~) is used to indicate the nasal sound represented by the letter “ñ” (e.g., “mañana”). Switch over to Portuguese, and the accent denotes nasal vowels (example: “cão” meaning dog).

Like its ancient cousin in the English book Doomsday, the tilde is still used in some languages today as a syllable break. It’s used to separate syllables or indicate a break in pronunciation.

Or, in Portuguese, it can appear over a vowel to indicate a separate syllable, such as in the word “sãbado” (Saturday).

But the tilde isn’t just found in traditional languages, like English, Portuguese and Spanish. The versetal accent is a favorite in the world of mathematics where it serves as an approximation or contraction. In the language of programming, the tilde can also be used to represent an approximation or a negation of a value. In some programming languages, it is used for string matching and pattern recognition.

As with all accents in languages, the tilde’s use can vary depending on the language, and its specific functions may differ from one context to another. Plus, since language is constantly changing, so will the uses of the tilde.

As for its use with the “ñ,” the accent will probably remain the same, despite the Spanish letter’s growing controversy.

On laptops and other computer keyboards, the ñ creates typing challenges as well. Some non-Spanish keyboards may not have a dedicated key for the letter “ñ,” making it less accessible for individuals who need to type in Spanish.

This has led to discussions and debates about how keyboards should be laid out. Today, technology must provide inclusion of the letter “ñ” in international standards, but reaching this agreement wasn’t easy.

In fact, in the 1990s, the European Economic Community (EEC) proposed eliminating the ñ to make keyboards more uniform. Spain had to fight for the ñ and its place in the world.

Even Spanish poet Gabriel García Márquez took the letter’s side in the battle, arguing that the “eñe” was not antiquated, but rather was an innovation that, “dejó atrás a las otras al expresar con una sola letra un sonido que en otras lenguas romances sigue expresándose todavía con dos letras.”

Ultimately, the argument between the EEC and Spain was settled by a clause in the Maastricht Treaty providing exceptions to protect cultural identity, according to the Cruces Sun News.

Today, the children of Spanish-speaking people in the United States are sometimes called generación Ñ. And national organizations like the National Association of Hispanic Journalists and the Cervantes Institute purposely have the ñ in their names.

And, it is important to note that neither the letter nor the sound ñ are exclusively in Spanish. In the Iberian peninsula, and even the U.S., the ñ is now widely used. Think of piña coladas.

All is an indication that the ñ is stronger than ever, as a letter and much more. … Yet, dozens of online articles still remain for those who still don’t know how to make an ñ on their keyboards, proving that the letter’s fight for equality isn’t over.