Image courtesy of Nuestro Stories.

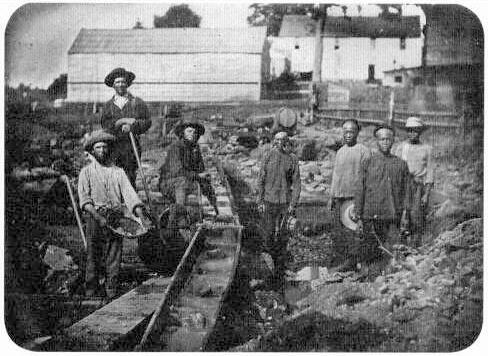

A meeting place for Mexicans, Russians, Americans, Europeans, and natives, the Gold Rush turned California into a veritable global frontier, drawing immigrants from every continent.

Between 1848 and 1850, more than 300,000 gold seekers flooded California, making the new state a tapestry of languages, religions, and cultures.

The call of the rush

When gold mines were discovered in California in 1848, the ethnic groups didn’t see what the fuss was about. But the rush was just beginning to heat up.

It wasn’t until later that year, just after President James K. Polk confirmed the existence of large sources of the precious metal that the euphoria exploded.

In the fall of that year, the first wave of Mexican miners traveled overland to California to join the gold rush. They numbered between two and three thousand and often traveled in entire families. By early 1849, an estimated 6,000 Mexicans were digging for gold. In California, a region that had so recently been theirs, the Mexicans found themselves considered foreigners by the legions of white miners.

The get-rich-quick race escalated, and tempers flared, giving rise to racial rejection, nationalism, and xenophobia.

The hatred that had been sown during the Mexican-American War finally bore its rotten fruit, and white Americans redirected their rejection toward Latinos who had answered the call of the rush.

However, Mexicans, Chileans, and Peruvians were far more agile in mining than their white counterparts, again putting civility to the test.

Californio Antonio Franco Coronel wrote, “The reason for most of the antipathy against the Spanish race was that the majority of them were Sonorans who were men used to gold mining and consequently more quickly attained better results.”

Rumors of thefts of up to four million dollars in gold spread like wildfire until General Persifor F. Smith, who was on his way to Monterrey to command the army, issued an illegal declaration forbidding anyone who was not a citizen from digging in the mines.

Smith’s declaration was not only unlawful but also erroneous: citizens were considered guests and were legally authorized to exploit public lands. However, this did not prevent the expulsion of a large number of Latinos.

When greed is stronger

To eliminate competition, in April 1850, California passed a statewide tax on foreign miners, which charged foreigners $20 a month to work in the placers.

The law was repealed in 1851, but it was too late; ten thousand Mexicans abandoned the mines.

The problem was also a matter of territory.

After the U.S.-Mexican War, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo granted the Californios full U.S. citizenship and a promise that their property would be respected.

In fact, eight Californios participated in the California Constitutional Convention of 1849. But over time, their political power declined along with their land base. With the imposition of U.S. rule in California, the elite gradually lost their power, authority, and lands.

The informality of Mexican land grants made legal claims difficult. They could do little when miners, squatters, and settlers began to arrive and invade the lands of the Californios.

One well-known case is the Peralta family, who lost all but 700 of their 49,000 acres in the East Bay to lawyers, taxes, squatters, and speculators. Getting legal title to the land bankrupted the families for legal fees or taxes.

Despite nativism and violence, the California gold rush also gave rise to cross-cultural cooperation and communication. Isolated groups first came into contact in the mines and streets of San Francisco, which would extend for years. California is now one of the most diverse places in the United States.